|

Have you a

husband who has only to hear the exhaust note of a sports car to forget

you even exist? Or one of those technical men who disappear as often as

possible under their own or anyone else’s car bonnets? Or even one of

those steady motoring men who fly out to the garage before breakfast on

Sunday mornings, bring the car round to the front door, and polish it for

the benefit of the neighbours?

Whatever

form their mania takes, if you are attached in any way to a motoring

enthusiast, read on – it’s always nice to know that others are suffering

too.

Every Friday

evening we leave London and drive home to our cottage in Norfolk, and most

weekends we leave our own Morris on some city bombed site and head for the

country in some car my husband has to road- test.

One Friday

recently David ‘phoned just as it was getting dark. “We’re having the

Lotus Seven this week. Be ready in half an hour and wear all the old

clothes you’ve got. Don’t bring any luggage – well just a canvas bag if

you must.”

We rattled

up to Hornsey in the Morris. “You’re not going too?” said Colin Chapman

incredulously.

“Where he

goes, I go,” I said bravely indicating David.

“You married

the wrong man,” said Colin and went away laughing. I couldn’t think why.

Funny though, he always uses a saloon car on the road. I took my first

look at the Lotus. It had a ground clearence, I am told, of five inches,

but it looked even less than this. It was painted primrose yellow and

everything was shining and new. There was a narrow space behind the seats

where the hood was stowed. David took one look at this and turned to me.

“Go and

throw out all the things you don’t really need, we’ll never get the case

in here otherwise.”

“But what

about the two bucket bags? One’s got the food in and the other, the shoes.

I am not going without my slippers!”

“All right

keep your slippers and leave the food. We’ll have to get some more.”

I obeyed in

anguished silence. After all it might not be so bad when the hood was up.

The seats looked nice, too, upholstered in red; and David always says the

air-stream is carried straight over one’s head by the windscreen. I began

to feel excited.

When I got

back with the much impoverished luggage, David was busy taking out the

seat-back and seat on his side.

“What on

earth are you doing?”

“I can’t get

in it unless I take the seat out.” David is six foot five, and the car,

Colin insists, was made for the “average man”, of five foot nine or ten.

“But you

can’t drive a hundred and twenty miles with your back resting on those –

those tubes.”

“Space

frame,” corrected David. Fortunately, however, he decided we could have

the seat-back in after all. He stood feet wide apart on the place where

the seat had been and then slid slowly down until, suddenly he was in. I

followed suit much more dexterously, and, with a roar, which seemed to

come out just under my elbow, we were off.

After the

first hundred yards my face was stiff and my eyes were streaming. I pulled

my scarf over my head and turned up the collar of my duffle coat. Before

we reached Enfield my clothes felt as though they were made of muslin.

“Exhilarating, isn’t it?” shouted David. His head came well above the

windscreen.

“Cold!” I

yelled.

“What?”

“I’m COLD!”

“I’m not –

where’s your spirit of adventure?”

I glared at

him through my goggles, and shrank down inside my rug as far as I could;

but as David put his foot on the accelerator and our speed increased to

seventy-five mile an hour, the rug was about as much use as Eve’s leaf

would have been on the top of Everest.

As I grew

accustomed to being an ice block, I began to look around me. I could see

the yellow bonnet stretching out ahead and watch the wheels turning under

the cycle-type mudguards. The road seemed very close and rushed away past

me like an endless grey ribbon. When we slowed for Ware I noticed that we

caused a great deal of interest and speculation, especially among the

young males of the population. I felt a small surge of pride in our

vehicle; no one else in the world could be driving one of these, after

all.

In Newmarket

we went into a very expensive hotel. There was a heavenly open fire, deep

carpets and soft lighting. I had a scotch and gradually began to thaw out.

We came in for some outraged stares from the other people in the bar, and

no wonder. David was wearing an old pair of flannels streaked with grease

and mud, a track suit windcheater, a pair of white plimsolls and a flat

cap.

“Going on

the Broads?” asked the publican staring at David’s footgear.

“No,” said

David, “just driving home for the weekend.”

“MG?” I

think the publican imagined he was being rather smart.

“No, Lotus

Seven,” said David.

“Oh,” said

the man blankly, pushing our drinks across the counter.

“Well, I

suppose you can’t expect anything else in Newmarket,” whispered David

fiercely as he came over to the fireplace. “They only believe in

one-horse-power here.”

However,

there was quite a good crowd around the car when we got back. In awestruck

silence the audience watched while we cocooned ourselves for the next

sixty miles. David let in the clutch, something seemed to push me

violently in the back, and we were out of the built-up area. The road from

Newmarket to Thetford is virtually straight and we cruised for mile after

mile at over 80 mph. As far as the Lotus was concerned there wasn’t any

other traffic on the road.

“Mind those

bends by Snetterton.” I shouted after Thetford.

“What

bends?” queried David.

“You know,

near the circuit – S bends.”

“We passed

Snetterton two miles back.”

I pondered.

“Well they used to be there in the Morris.”

Perhaps it’s

just that in the Seven there’s absolutely no roll on the corners – the car

just sits down and goes on as if the road is dead straight. Fifty minutes

after leaving Newmarket we were in Norwich, and ten minutes later we were

home.

We usually take our time about getting up on Saturday mornings but not

this time: “Come on leave that washing up,” said David after breakfast,

“we must go and do some acceleration tests.”

“What in this weather?” The frost had given way to a steady drizzle and

the outlook was grey, cheerless and WET.

“It’s almost stopped – the road will dry up in no time. Come on it might

rain all day to-morrow.”

I went to fetch my duffle coat; the sight of it should have warned me. The

left side was delicately sprayed with dirt, fine gravel and sand. Oh well,

there’s no point in making a second coat dirty. I put it on somewhat

grimly.

As we turned out of our lane and David accelerated, we went through a

large puddle. Muddy water shot all over the windscreen, me, the back of

the seat, the new hood lying in its luggage space, everything. On opening

my eyes again I found I now had a smart two-coloured coat, dark brown on

the left, yellow with brown spots on the right. I was so filthy it

didn’t'’ matter any more, so I sat back against the rivulets running down

the back of the seat and wallowed in it. There is a conveniently deserted

wartime airfield near our cottage, just the thing for tests and learning

to drive, or slow bicycle races. The runways are in a bad state but the

perimeter track is reasonably smooth and uncluttered. But last Saturday

morning it was terribly wet.

0-30 IN 3.8 SECONDS

David handed me the stopwatch. “Usual stuff – the speedo’s just been

corrected, so we’ll give it the benefit of the doubt.” We shot off in a

cloud of spray, wheels spinning madly in the puddles. The speedometer

needle flew round and I almost took the skin off my finger in my anxiety

to press the catch properly. “0-30 3.8 seconds, 0-50 9.8 seconds,” I

announced.

“Not good enough, we’ll do it again.” Half an hour and a great deal of

water later, David decided we had had enough. The figures were just the

same as the first ones. I handed back the stopwatch and wrang out my

headscarf. “What’s that sloshing noise?”

“I think we’ve acquired a built-in lake and I’m sitting in it,” said David

happily.

Our sitting room was looped with clothing like a stall in Berwick Market

for the rest of the weekend.

The Lotus came in for a great deal of attention from our friends and

neighbours. A farmer in the village approached it cautiously and walked

all round it, staring gloomily.

“What speed does it do, d’ya say?”

“Only about ninety,” David said – “this is a poor man’s car, you know, but

it would probably do 120 with an ohv head on the engine.”

“Oh ah.” This is a Norfolk expression which can be used to cover doubt,

assent, interest, disinterest, or just plain disbelief. Our farmer friend

managed to imply mournful disapproval of the follies of youth.

“Good brakes?” He went on.

“Marvellous,” we said in unison.

“Need to be at that speed. What happens when you come up fast behing a

lorry? Zip! Under you go, off comes your head.”

He shook his head sadly, prodded a front wheel with his stick, and stomped

back to his farm.

The reaction of a sporting friend who turned up during the afternoon in

his red Frazer Nash was very different. He drifted to a halt in our

gravelly lane and practically fell out of the driving seat.

“Now that’s a real car! Makes this look like a bus,” he said indicating

his beautiful, gleaming Nash.

The boys at school where David used to teach said, “Sir, sir, how do you

get in it sir?” and “Please sir, is it a sewing machine?” and proceeded to

hide it under a bush while we were talking Rugger in the Staff Room.

We drove the Lotus back to London on Monday morning. The sky was heavily

overcast and grey, but it was dry, and I had learned a thing or two by

this time. I wore more clothes. I had turned out a woolly ski-hat which

came over my ears; and I improvised an effective sidecurtain for my side

from an ancient deflated Li-lo air bed. With no spraying mud or water, and

far less wind, I thoroughly enjoyed the journey. It was lovely to be in

the open air, now it was milder, and in the daylight I could truly

appreciate the terrific acceleration and incredibly good road holding of

the little car. “What tremendous fun summer-time driving in a Lotus must

be,” I thought. I began to sing. David looked at me curiously.

“You’ve changed your tune haven’t you? I thought you hated the sight of

the car, you’ve been moaning enough.”

“Yes, well . . . one gets used to anything, I suppose.”

I wasn’t going to tell him I liked it – he might have gone and bought one!

Perhaps in the summer, perhaps . . . I might even buy one myself!

JWW

|

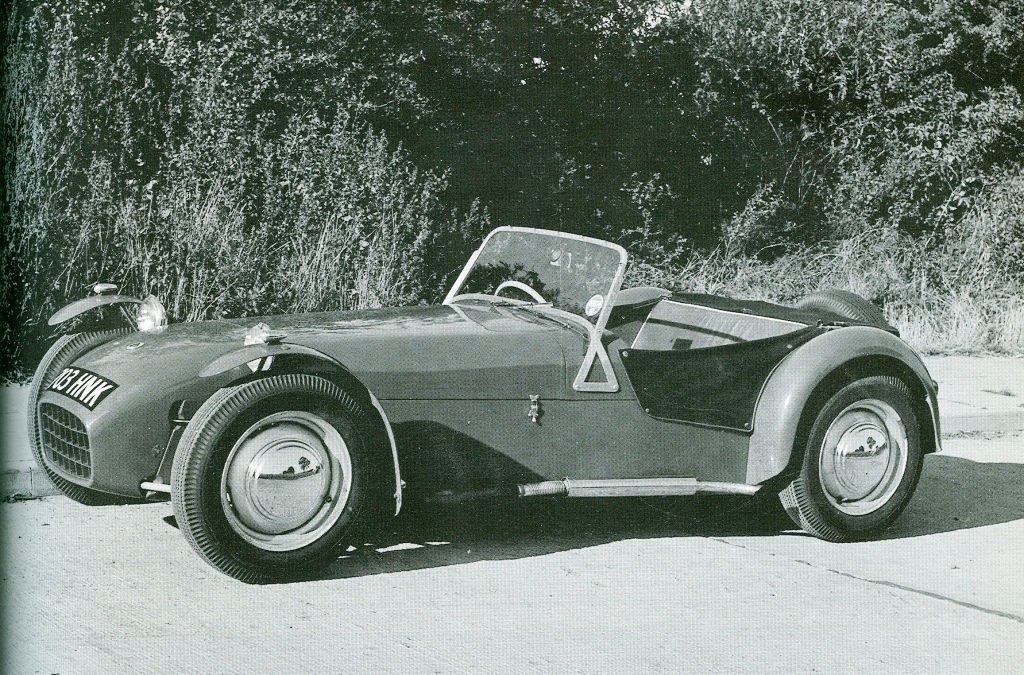

Typical car used for this road test.

Typical car used for this road test.